Williamson, Kohli and the beauty in romance of likability in sport

🔍 Explore this post with:

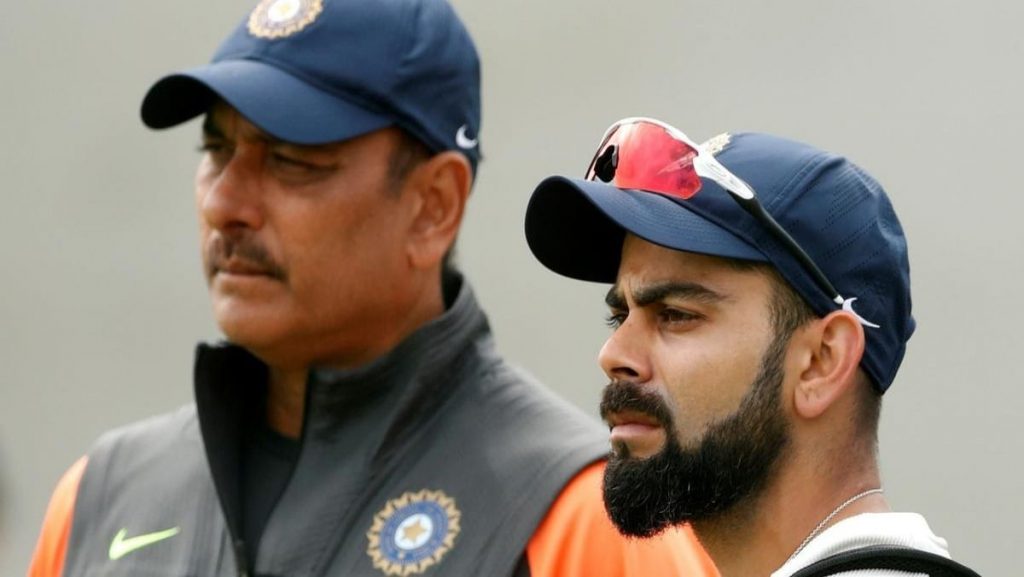

As Ross Taylor whipped Mohammed Shami to the midwicket boundary, an air of triumphant anti-climax descended across The Rose Bowl. Most of the scattered crowd who were still around to perhaps make sense of the pounds they had spent, the pandemic they had braved and the rain they had outlasted had started making their exits. The few left behind – no more in number than an extended Indian family – were bare-chested Kiwis, marvelling in equal parts about the belated arrival of the English sun and disbelievingly coming to terms with Williamson triumphing over Kohli.

Not too often in life do we come across people experiencing moments that are so overwhelming that the recipient knows not how exactly to react. In general life, it would be like capturing the reaction of a farmer if he was to receive the due he actually deserves for his crop. In football, it is like watching N’golo Kante being embarrassed at his French brethren singing his name to the tunes of Les Champs-Elysees by Joe Dassin.

That is exactly how the picture of Kane Williamson hugging Virat Kohli came across. Throughout the course of the buildup to the WTC final and during its stop start eventuality, the broadcasters likened profound human qualities to Williamson and Kohli in a weirdly anthropomorphic way. Fire to Kohli’s brisk pace of walking and ice to Williamson’s leisurely stride. However, not much was made of the said image, which juxtaposed everything abstract sport represents today.

Williamson and the narrative of “niceness”

The victor almost bowing to sink into the chest of the opposition in embrace – almost as though in apology and perhaps even in empathy – characterized the man within.

Here is someone who has felt the piercing pain of defeat after touching victory on the tip of his fingers. It was in his grasp, and yet it was not. Enduring two ICC World Cup final defeats had perhaps hardened Williamson to be averse to any emotion. Worse still, it has perhaps evacuated the conscious mind of the image of Promised Land.

That would explain the concoction of befuddlement and delight bodied by Williamson in victory. This would continue to the serenade where he, in the company of his team, lifted aloft the ICC Test mace. They were world champions but you would not quite believe it. And they were trying their best to that end. Not consciously, but that is just how these people are. Williamson and New Zealand are “nice” people and if you did not know that already, cricket Twitter would fill your stomach up to your larynges with platitudes like “nice guys don’t always finish last”.

But what is this “nice” guys narrative supposed to indicate. What defines a nice guy and why is it so important to be nice in sport. Some would even argue that niceness is counter productive to success in a discipline where one has to win at the expense of the other. It is difficult to quantify what nice comprises in sport.

However, there is still no denying the happiness of people at the victory of New Zealand. This is a team that lost out on two ICC finals – one against Australia in Australia and the infamous Super Over reversal to England at Lord’s. Thus, people were happy seeing New Zealand finally win the big trophy. This was a similar situation Sri Lanka were in, in the final of the ICC World T20 in 2014. They had lost the 2007 and 2011 ICC World Cup finals to Australia and India, respectively.

Why is Kohli not “nice”?

Like with BJ Watling and probably Ross Taylor in the WTC final, Sri Lanka had two of their finest retiring on the day of the 2014 final. Coincidentally, it was once again at India’s expense that Sri Lanka won that World Cup.

Since 2014, in fact, India has been to the semi final of every ICC event – T20, ODI and now Test matches. However, the same public sympathy does not seem to accompany Virat Kohli and his men. In fact, even in his very country, Kohli has public downfall wishers. Almost all of them implicate a common narrative – “arrogant and boisterous”.

Therein lies the focal point of the inexact science of “niceness”. What the wider world in extension to his on-field personality in direct comparison to Williamson’s believe Kohli to be is the opposite of “nice”. But here is a man who, man of the tournament in the 2014 T20 World Cup, went up to Sangakkara and Jayawardene to congratulate them after defeat in the final. He wrote a letter to the former after his retirement from ODI cricket in 2015. Kohli even won ICC Spirit of Cricket Award in 2019 for publicly, in the midst of an India Australia World Cup battle, signalled the crowd not to boo Steve Smith.

Kohli is the same man who gifted Tendulkar a very valuable thread his late father had given him. Kohli had said, there was no better way to quantify Tendulkar’s invaluable contribution to Indian cricket. AB de Villiers had once recounted an incident when Kohli had randomly gifted him something he had, in casual conversation mentioned, he wanted.

These are all very “nice” gestures from someone who would be just fine without doing them. The volume of runs he has scored and the number of games he has won as captain would be enough to have him on the posters and get him all the brand deals. But perhaps all this media attention pointing towards the emotions of Kohli, which manifests itself malleable to situations is why public perception towards him is different.

Kohli and a victim of association

Perhaps also a word needs to be said about his association. The world, today, has evolved to the end that patronizing statements do not fly anymore. India as a nation is progressing to form opinions of their own and challenge norms. The common folk, now unburdened from having to brick and mortar build a nation, has more time on their hands to understand finer nuances in life. They do not fancy being told what to do. They see something and want to form their opinions. In fact, making bold claims now translate to a disrespect of past achievements. People now are more open to embracing the greys of life as opposed to the binaries.

That is perhaps why statements like “bigger than 1983 World Cup victory” and “best travelling team of the past 15-20 years” do not go down well with the public. They want to experience victories and form their own opinion of them. These statements now drive public opinion against the speaker as opposed to forming them in coherence with the ideas propagated.

It is akin to movie actors being stereotyped by the roles they play. Sports personalities are boxed by how they play the game and what they say in public appearances. Should they be? That is a complex question. But there is a public need, an innate human nature, to make sense of everything. And so, people perceive sports people to be what they see on the field and hear on the microphone.

But there is only as far people are willing to go with their analysis. Perhaps time or a limitation of imagination makes general public opinion a case of neither here nor there. People will neither stick to just being a fan, nor will they make the effort to deep dive into what an action truly means. The final perception is thus a lazy middling attempt amounting to half-baked partial truths formulated only to fit agendas.

But these agendas influence public opinion. Perhaps the person is making bold statements only to egg his players on, but his on-screen persona and his words together paint a picture that does not make him likable. It seems as though he is disrespecting the past in order to validate and quantify the present. That becomes counter productive to the honest joy people want to experience. By planting comparisons in the mind of the public, they cannot feel the pleasure of one achievement without comparing it to another. And comparisons always pale achievements – of either the present or the past and sometimes, both.

Williamson, Kohli and the romance of likability

These statements, especially in context to Williamson’s post-match interview after winning the WTC final probably quantifies the “nice” guy narrative explicitly. “I’ve been part of [NZ cricket] for a short while, it’s a very special feeling,” said the Kiwi captain after being prompted to call the victory their best ever in history. It was the first time in New Zealand cricket history that they became a world champion, but nothing from Williamson’s statements or body language would seem to signify “flashy”.

But would it be wrong? These players work their entire childhood and teenage, sacrifice a normal teenage life with friends and outings and burgers and calories to become professional athletes. Then, they compete with elite athletes across their nation to qualify for the national team. Then they compete with the best the world has to offer and finally, after all the sacrifice comes the victory. People are allowed to be boisterous and brandish stupid dance moves or say cheesy one-liners.

And it is then that you realise, everything boils down eventually to the perception of beauty in romance and likability. Nobody can ever script it or lay out a road map on how to achieve it. It is all very abstract. That is exactly why the picture of Williamson stooping to sink into Kohli’s bosom signifies so much more than just a gesture.

It signifies the romance of likability and at its core lies the ability to capture the gaze of the subconsciously partisan watching world who are waiting to feel conflicted. It is true for all sport. Wanting to support Hungary as they are the underdogs but realising their government has passed anti-gay laws. Wanting Djokovic to enthral you with yet another service return but realising he is getting closer to your GOAT claimant.

Similarly, New Zealand played the WTC final only because other teams could or chose not to compete in the pandemic and ICC changed rules midway. They benefited as other aspirating teams fell foul of a microscopic virus. And yet, they are the “nice” guys the world wanted to see winning.

Meanwhile Kohli, despite everything wonderful he does, and facing similar heartbreak at ICC knockouts will never be good enough for love of that ilk. And yet, the world cannot do without Kohli and his team. There is perhaps a bit of romance in that too. The romance that loves to hate. It is almost akin to the days immediately following heartbreak caused by our first love during our teenage years. Cannot do with and cannot do without.